Thoughts on ad blockers

Tuesday, September 22, 2015

Most of this article is an extensive discussion of my hunt for the best ad blocker on iOS. It isn’t exhaustive and, given the pace at which the App Store moves, probably won’t remain current for long. That’s why I want to open things with my own thoughts on ad blocking, because I don’t expect those to change any time soon.

My Opinion on Ad Blocking

Large publishers don’t have much to worry about with regard to ad blocking because they have the resources to play cat-and-mouse with developers. But smaller publishers and even independent publishers of a significant size, traffic-wise, are right to keep an eye on ad blocking. I don’t think John Gruber has much to worry about either, but he also doesn’t have time to spend staying one step ahead of blockers who blacklist his primary advertising network, The Deck.

I use blockers on desktop browsers and, now, on iOS for all the reasons so many people have already cited: ads often ruin the reading experience, trackers build creepy profiles on what we like and follow us around the web showing it to us, and sometimes the stuff a publisher publishes is worth our eyeballs, so why should we be counted among their visitors and help boost their ad rates?

But… But… But… BUT…

Can you sense that I’m about to state a caveat to my support of the development and use of blockers? If not, you need more coffee, or to visit a doctor, or just give up reading for, like, ever.

Seriously though here’s the caveat: Blockers should absolutely always and without fail include a whitelisting feature, and it is my personal opinion that to use blockers without actively using the whitelisting feature is entitled, unethical and hypocritical.

It’s entitled because it assumes you deserve everything published on the web for free, just because, like, you’re you. That’s not true.

It’s unethical because there are absolutely jobs to which blocking poses an existential threat, and jobs are people, and people have families, and feelings, and futures.

It’s hypocritical because, at least in my mind, the primary purpose of using blocking tools is to say to publishers and their ad partners, unequivocally, you’re doing it wrong. But to say that sincerely you have to have in mind that there is a way of doing it right. And, of course, there is: unobtrusive, minimally tracking advertisements carefully monitored and held to a far higher standard than that to which most are held these days.

It sends no signal to simply block everything indiscriminately, which is what you’re doing if you don’t use a whitelist. I want publishers who display ads respectful of their readers to continue to be able to sell that inventory. I want to see a virtuous cycle: I want them to be able to charge more for that space because they’re on whitelists their less respectful competitors aren’t on.

So I use ad blockers on desktop and mobile, and also spend a lot of time on building whitelists full of sites whose ads I don’t mind and whose business model I want to help preserve for at least as long as it takes for them to find and transition to whatever model comes next.

An Ad Blocking Case Study: Peace by Marco Arment

Apple released iOS 9 earlier this month and Safari, the built-in browser, gained the ability in 64-bit devices to load what Apple calls (a bit disingenuously…) “content blockers”. These are apps you install and enable in Settings > Safari > Content Blockers. This new class of apps is almost exclusively used for blocking display advertisements and tracking scripts that follow you around the web building an anonymized-but-still-targeted-at-your-face profile about you.

I’m writing this to express my opinion, because that’s what the internet is for. I’ll explain my reasons and then recommend steps you should or shouldn’t take based on how much you agree with me.

[caption id=“attachment_1388” align=“aligncenter” width=“576”] Settings screen from Peace, an iOS ad blocker by Marco Arment[/caption]

Settings screen from Peace, an iOS ad blocker by Marco Arment[/caption]

Let’s use a case study to illustrate the acceleration of the debate about ad blockers on iOS and desktop web browsers. Marco Arment, an early tumblr employee, the creator of Instapaper (which he later sold) and, more recently, of the Overcast podcast service for iOS, released his own ad blocker, called Peace, on September 16, 2015, announcing it in a blog post. He explained in that article:

And we shouldn’t feel guilty about this. The “implied contract” theory that we’ve agreed to view ads in exchange for free content is void because we can’t review the terms first — as soon as we follow a link, our browsers load, execute, transfer, and track everything embedded by the publisher. Our data, battery life, time, and privacy are taken by a blank check with no recourse. It’s like ordering from a restaurant menu with no prices, then being forced to pay whatever the restaurant demands at the end of the meal.

I was one of many purchasers who paid $2.99 to try out Peace on my iPhone, helping to send it flying to the top of the paid app charts almost immediately. It’s well-designed and includes the ability to do one-time exceptions or permanently whitelist specific sites (more on that later). Arment had to explain in a post the day after Peace launched why Peace blocks the classy ad network The Deck. This explanation was important because Arment displays advertisements on his own site using The Deck. It was a clear example of the cognitive dissonance the ad blocking issue causes.

The Top App Disappears From the App Store

The day after that, though, Arment did something surprising: he pulled Peace from the App Store and explained how everyone could get a refund. That’s tens of thousands of dollars to which he said “Nevermind” because he developed a crisis of conscience. He said:

Peace required that all ads be treated the same — all-or-nothing enforcement for decisions that aren’t black and white. This approach is too blunt, and Ghostery and I have both decided that it doesn’t serve our goals or beliefs well enough. If we’re going to effect positive change overall, a more nuanced, complex approach is required than what I can bring in a simple iOS app.

Arment can afford to take the hit, financially, but what’s more surprising about this move is that he is a world-class iOS developer, constantly improving and maintaining a popular podcast app, who spent a lot of time and effort and stress building an app that, only days after it launched, he decided to kill. And Apple took notice: the company notified him on September 21 it would be “proactively refunding” every purchase of his ad blocker.

I didn’t expect that because Apple included in iOS 9 its very own News app, which doesn’t allow content blocking and thus is now the only bullet-proof way for publishers to ensure their advertisements come along for the ride when someone reads their stuff. I wonder if it was more a kind gesture to Arment, whose great apps bring a lot of attention and a nontrivial amount of money to Apple (who gets 30 percent off the top for every purchase of every paid app) and iOS.

The First Crop of iOS Ad Blockers

I tried five different ad blockers1, listed below:

I quickly realized my dealbreaker feature while evaluating those apps: whitelisting. That immediately eliminated AdMop and Crystal.2 The next one I eliminated was Blockr which, while it does offer a whitelist, is a little too complex for my tastes, requiring you to choose from several different elements to whitelist on each site. I prefer simplicity just from an aesthetic perspective, but more importantly “normals” – non-geeks – are less likely to use a feature that looks complex and bloated, not because they “don’t get it” but because they’re not obsessed with spending hours tweaking the settings on their gadgets.

Peace is my favorite because not only does it offer a whitelist, but the action extension you use to whitelist a site includes all of Peace’s other settings, including a global disable button. Even more interesting is the separate action extension Arment included to “Open in Peace,” meaning you can disable the app globally and selectively load overburdened pages in Peace on demand. While I’ll focus on building a whitelist, the inclusion of a selective-enable option demonstrates the amount of thought Arment put into this issue. This wasn’t just a money grab, it was an experiment. That’s what the Scott Meyer, CEO of Ghostery, the company whose blocking database Arment licensed, called it, The Peace App Experiment. His thoughts echoed Arment’s:

Specifically, the black and white, all on/all off approach to content blocking in Peace ran counter to our core belief that these aren't black and white decisions. With the currently limited flexibility of the user experience, we both felt it best not to continue to sell or support the app. Ghostery is based on giving the consumer the choice as to what they block and when. Ghostery doesn’t block ads or any other content by default. That’s too subjective a call. If there are objective measures for what types of tracking should be blocked, then that’s an option we’ll pursue. Right now, however, we didn’t feel that we had the mix right in Peace. Marco agreed.

I suspect based on that language and Arment’s own post about withdrawing the app that future improvement by Apple to its blocking framework may enable the nuance to which Peace aspired. For now though, the app isn’t available anymore and, while if you already have it installed and don’t delete it, you can keep using it, there’s no guarantee of any support or updates. I plan to hang onto it and will probably stick with it until Purify somehow differentiates itself.

[caption id=“attachment_1387” align=“aligncenter” width=“576”] Whitelisting screen from Purify, an iOS ad blocker by Chris Aljoudi[/caption]

Whitelisting screen from Purify, an iOS ad blocker by Chris Aljoudi[/caption]

But for those of you who haven’t yet tried one out, or are still on the fence about which one to use, and haven’t yet purchased and installed Peace, or have deleted it since it was pulled from the App Store, I have to recommend Purify. Yes, it’s $3.99, no, that shouldn’t stop you from getting it. It has a dead-simple and fast whitelisting option and lets you decide to block images, scripts and fonts as well, although only ads and trackers are blocked by default.

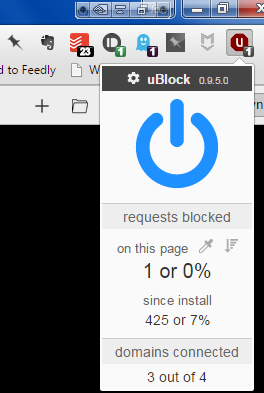

[caption id=“attachment_1390” align=“alignright” width=“264”] ublock, an ad blocker for desktop browsers, by Chris Aljoudi[/caption]

ublock, an ad blocker for desktop browsers, by Chris Aljoudi[/caption]

Purify also has the benefit of being developed by Chris Aljoudi, maker of the uBlock extension for desktop browsers. uBlock also has a dead-simple whitelisting option. Aljoudi developed uBlock out in the open and it’s free, so you can get a good sense of the quality of his work before buying Purify, if my recommendation isn’t enough.

iOS 9 marks the first time Apple has included content blocking in the mobile operating system, and it almost certainly is part of a larger strategy to squeeze other large companies reliant on advertising models for revenue. But its bound to put pressure on small and medium publishers to clean up their advertising standards or consider alternatives like membership programs or tip jars, used by Brett Terpstra, The Loop, Katie Floyd and many others, with varying degrees of success.

For now, I’ll keep on blocking the crap and whitelisting the good guys. How about you?

Feature image by NEXO Design under CC-BY-SA; screenshots by me

- There are many more, and the field will no doubt continue to grow. See Dave Mark's list at Loop Insight. He posted his own thoughts on all of this the next day. ↩

- Crystal has a "Report Site" action extension, to tell them about sites that break with Crystal enabled, but no whitelist. ↩